Researchers claim to have found a way to protect yeast from damage inflicted by pretreatment chemicals in the biofuel production process.

Pretreatment chemicals are used in biofuel facilities to accelerate the breakdown of plant material, however, these chemical are sometimes poisonous to the yeasts that turn the plant sugars into fuel.

In a study published in the journal Genetics, a team from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the US Department of Energy claim to have identified two changes to a single gene that can make the yeast tolerate the pretreatment chemicals.

“…the process of decomposing plant material is really slow. It takes years for a fallen tree to completely decompose,” says Trey Sato a senior scientist at the UW Madison based Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Centre and lead author on the study, in a media release.

It is for this reason that biofuel manufacturers pre-treat the raw biomass to speed up the process. This can include applying ammonia gas, acids, heat and pressure, ionic liquids.

The next step in the process sees microbes used to ferment the sugar into fuel.

“Those ionic liquids are useful for pretreating and getting the process started,” Sato explains in the statement.

“The problem is that even after you go to the trouble to remove and recover as much of the ionic liquids as you can from your biomass before you do the fermenting, the amount you can’t get out is enough to be toxic to a lot of microbes.”

This toxicity is enough to make the yeast up to 70% less efficient.

(If you want to start bio diesel business, please click!)

Solution

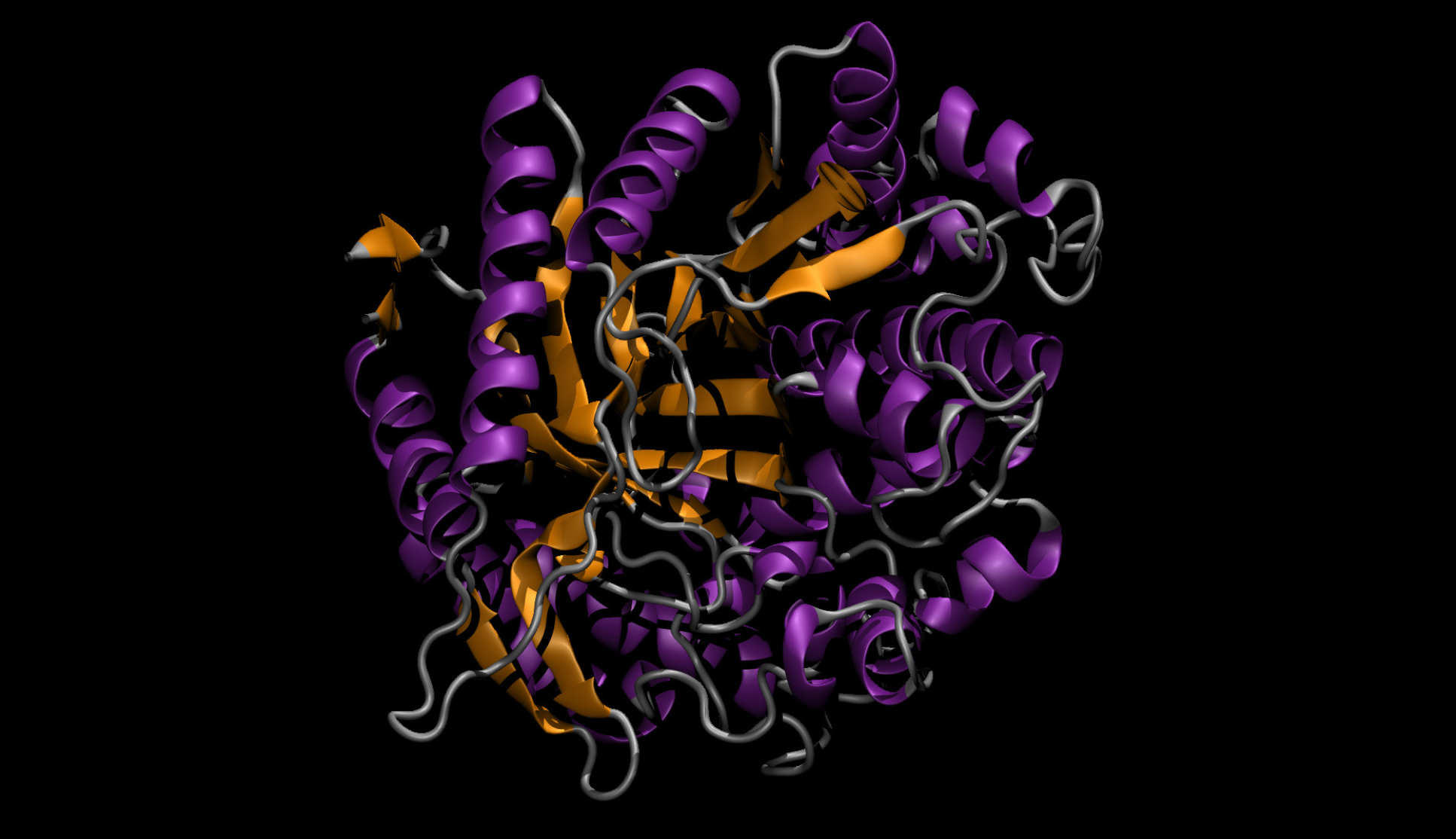

The researchers surveyed 136 isolates of the S. cerevisiae strain, finding one that had ‘outstanding’ tolerance to ionic liquids. Screening DNA sequences from this strain, they identified a pair of genes key to surviving the otherwise toxic pretreatment chemicals. One of them, SGE1, makes a protein that settles in the yeast membrane and works as a pump to remove toxins.

“If you have more of these pumps at the cell surface, you can get more of the ionic liquid molecules out of your cell,” Sato says.

The team used the gene-editing tool CRISPR to alter a strain of an ionic liquid-susceptible yeast, introducing two single nucleotide changes that increase the production of SGE1. In doing so they produced a yeast that can survive and ferment alongside amounts of ionic liquids that are usually toxic.

“Now anyone using this yeast can look at a specific gene in their own strain and tell whether it’s compatible and useful with an ionic liquid process or not,” says Sato.

“It’s a simple engineering procedure, which doesn’t take long and isn’t expensive. And it can be fixed with CRISPR in a matter of a week or two.”